Talking money lessons with my mother

The matriarch of my family opens up about our history with money.

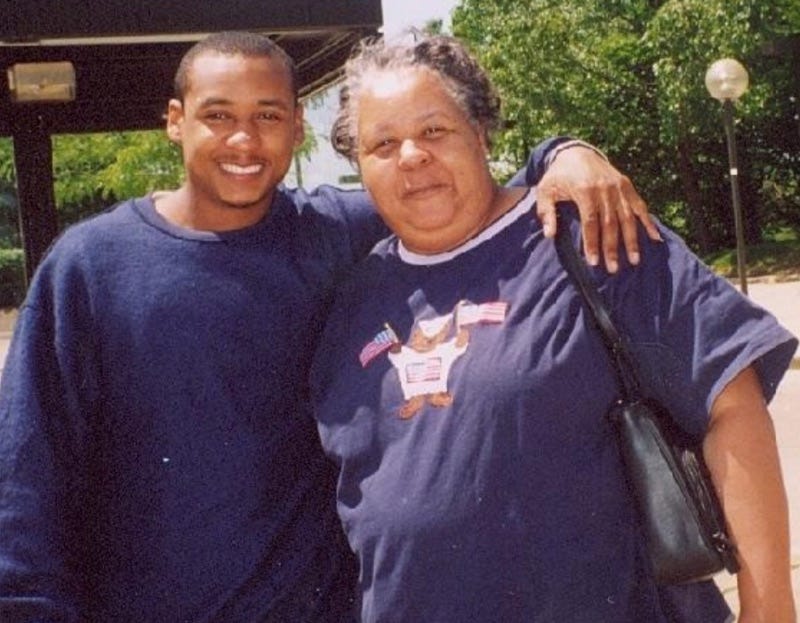

If my daughter Parker was my all-time favorite interview, my mother was my toughest.

I’ve never shared that with her until now.

While I’m forever thankful for her willingness to be a part of this project, I had no idea the emotions our chat would conjure as she reached way back to recall mostly bitter memories. She didn’t have to do it. Her vivid examples, so easily summoned all these years later, only reinforced the depths of our family’s financial trauma.

It was painful at times to hear, infuriating whenever my thoughts invariably drifted to why our family’s hard work wasn’t enough.

But it was a priceless conversation. There are lessons to be learned and a wealth of wisdom that my mother, through a life of trial and error, hardship and triumph, has openly shared.

This was the mother of all “Money Talks.”

Here, in her own words, is my 74-year-old mother, Alberta Mayberry.

My father graduated from high school and went into the Navy. He came out and worked a couple of small jobs and then he signed onto Shell oil company. And he worked there, I’m thinking, 42 years. And it may have been more than that. He retired from Shell. He was in the mailroom and a porter. Moving things from here to there, through the office.

But he also did lawn work. Bartending and party service. And dad did taxes. And I thought he was getting paid for doing people’s taxes for them. I came to find out from a friend of mine — he and I sat under dad and learned how to do income taxes — he never charged anybody. That was one of his ways of giving back.

My mother, on the other hand, was a full-time housewife and mother. Eight children. But on occasion, she worked for a florist delivery. And she worked for a dental service where they made teeth. She would do delivery there and cleaning there. So she basically did domestic. Sometimes she’d go out and help dad serving parties at the River Oaks’ houses.

We knew that we were poor. But we knew that we were better off than some of our neighbors. It was not a disgrace, but we had to go through and, like we host a pantry here, we had commodities. That’s what they called them. And so we lived on what we grew, what we raised, what was given to us by others. And commodities. And then some minimal grocery shopping because food had to be stretched. And so you stretched it by just getting what you could.

We really didn’t have sit-downs and say how much money we brought in and how much money had to go out for lights and gas and all of that. The old line, ‘You must think you live in a barn. Close that door,’ or ‘Turn those lights off. You don’t know how much electricity costs.’ But not sitting down looking at a budget and saying, ‘We only have this much to do this with. We need to be saving for our one-in-every-10-year trip to California.’ We didn’t do that. That was adult business.

(My brothers) Shelby Jr. and Marvin worked with Dad on housing projects and renovating houses. And they didn’t get paid for that. They didn’t get an allowance for that. That money went into the family income.

Want. Just the word want. There were so many things that we did not have that we saw other people having. There was so much that we wanted that we could not get and we knew we couldn’t get it. Even if a babysitting job came through, that money went to my mom and dad.

I didn’t know how much my dad made on his job at Shell until I got my first job at Texas Southern. And after his 30-plus years, I found out I was making a couple of thousands dollars more than he was making.

And you didn’t ask for money that you knew your parents didn’t have. That was embarrassing them. So we didn’t even request, ‘Can I go to the movies?’ ‘Can I get a new dress for this program?’

And so hunger. I think that’s a part of my lasting addiction is hunger. Not being able to have. (My sister) Clara never really expressed that until it was time for her to go to college. And she really wanted to go to either Hampton or Dillard. She wanted to go to one of the better HBCUs. She did not want to stay at home. And there was just no way our parents could afford it. And so she just, without even consulting them, she went and joined the Air Force. Those are the kinds of things I remember.

I thought I was not going to have a nice dress for my first National Honor Society program. My mother stayed up all night long to make sure that I had a dress for National Honor Society.

Hand-me-downs. You know hand-me-downs. One person has it, and you better take care of it because the younger sibling is going to have it. You got a new pair of shoes for Easter. And if they did not last for the beginning of school then you got another pair for school. And that was about it. And you had to hold onto those things.

I think that there are three basic things that my parents taught me. I’ll say four. Be honest in how you get money. Don’t lie. Don’t cheat. Don’t steal. We’ve heard that before, haven’t we? So work hard to get your money. Be good stewards and very charitable through your church or through helping others. The two investment items were buy property and use the equity of the property to buy other property. And then the last one was the one that I think impacted me the most which was build your retirement from the start. Start putting money away for retirement.

I guess the other one is self-sufficiency. As in, if you can cook it, don’t go out and buy it. Cook food. If you can make a dress, make a dress. If you can cut your yard, don’t hire anybody else to do it. So make that five, self-sufficiency.

I’m going to try to describe (my money habits) in three parts: As an adult with children without a second income — a co-parent in the home. As an adult working and things getting better. And then as an adult now.

My time with money while I was raising you guys was almost nightmarish. My fear of not being able to feed and house and take care of you guys.

I told somebody one time prayer was my medical plan for the time we were at Bishop College. It was strictly praying to the Lord that nobody gets sick. Because Bishop had health insurance and then they didn’t. They went bankrupt and we were working like sharecroppers. We were working, and if some money came in they paid us. And if it didn’t, they didn’t. And I got another job. And other people got other jobs. And we did what we could to commit to that college.

But I was afraid all the time that something bad was going to happen and I would not be able to take care of my children.

I think I took better care of myself and better care of my clothing, and I was a better steward of what I had. Because I couldn’t get no ‘mo. I couldn’t run out and buy some more. Because I didn’t know if I was going to have the money to pay for it.

If I haven’t told you the story about the Conoco card. The first couple of months we were at Bishop, I had to use a credit card. To buy stuff for lunch. For breakfast. For gasoline. You could cash it for $10 over. And so a little bit of cash. That is the most ridiculous way to live in the world. And then you pay that off as soon as you get a check to come in. And then you do that all month again. It was just, like, ‘You can’t live like this.’

Finally, we got past that to where we had regular money coming in. And I think I loosened up some. Probably the better thing would have been to stay on that strict budget, or non-budget, that we had. But I didn’t.

As I got into a situation where I had more money and the job was paying off on a regular basis and I wasn’t fearing missing a paycheck, I was fearing it being late. Because I was living from paycheck to paycheck. And I could have prevented that but I didn’t. Because there was so many things that you all had not had that it was my time, I thought then, and you all were older, to give it to you. To make sure you were in Little League football and baseball and just the gas to take you back and forth. That was consuming.

And then I’ve told you about the time we realized we were not waiting for the check to drop. Because we still had some money in the bank, Doc [my late Godfather] and I.

When you get to that point, it’s almost time to celebrate. Not to buy the necessary things but to celebrate. And I don’t have to go and buy the reduced chicken and the reduced bread. I still do. But I didn’t have to. The problem was I’d buy more of it.

I went from being very stoic and a good steward of the small that I had to a splurger because I had more. And it’s not necessary to splurge. We were eating fine. But all of a sudden, I decided to splurge.

And saving money only started in my true psyche when I got the job with the State Department. Because I was making more money then. They were paying for a lot of the stuff that I normally would have had to pay for. But I did have two boys in college. And then I had two more boys in college.

(I taught my children) to get it earnestly. Honestly. To be charitable. Go back to ‘Work for it.’ If you need something, you want something, you need to work for it.

All three of my older sons were told at the age of 16, ‘Go get a job.’ But then there was this youngest son that I had who decided, ‘I ain’t getting put out the house. So somebody went out at 15 1/2, I think it was, to get a job.

That was a mainstay for me. Get a job and work for what you want over and above what it is I can give you.

Give money back to the church. And save money for what you want to do. I didn’t say, ‘Budget.’ But I did say, ‘If you know you want to go somewhere, a dance or whatever, you need to put that money back now so you can go there.’

I’m learning so much more now that I did not know that it was something that I could know. How to invest. Why to invest. What to invest in. Better ways to save than what I was doing.

I never got caught up in the high-interest credit card thing. I would always pay more than the minimum amount. But I wish that I had known back then what I do now, and that’s to use that credit card as a debit card and pay it off. And take advantage of any of the perks that these financial plans give you. But then pay it off. Don’t let that debt linger and last for a long time.

Not to be trusting of other people with your money. That’s one that in later life has bit me in the butt. Somebody comes with a great line of how it’s going to help, and it’s going to do this and it’s going to do that. And all they’re doing is letting you buy them some future income. The two annuities that I have could have been better placed, and I now know that.

There are people who are called fiduciaries who are bound by law not to take advantage of you. I wish I had known that so that I could have been trusting and could have gotten more out of the money that I had. To save. And to leave. And to invest.

I liked the part of real estate that my parents did. I’ve owned three houses, and I understand now that my way of building wealth on real estate was not as easy as theirs because they had the manpower and the knowhow to fix those houses. Anything I do here, it’s money going out and no money coming back in for it. So realizing the value of that lesson that they taught did not work for me.

Everything that somebody else does to make money does not always work in your own situation.

I am extremely happy that I came out of college more or less debt free. All of my colleges. And I have tried to instill in my sons, number one, ‘Go where the money is.’ Number two, ‘Get that work study job. Do whatever it is to help keep that debt down while you’re in college so you walk away without having that hanging over your head.’

I wish that I had extended myself to use the intellectual skills that I had. Not for working for somebody else. But for speaking engagements. Paid speaking engagements. I spoke a lot, but they were not paid. That was not smart. People were getting paid, and I was not.

I did not turn my dissertation into something that was marketable and a cash flow. It should have been a cash-flow object.

I did not put making money, other than working, into any category that was more helpful to me than work a 9-to-5.

There’s going to always be an emergency. A medical. A legal. Something is going to raise its head that’s going to make you have to think how to pay for it, whether or not to pay for it, whether to live without it. And I don’t think I was ever as prepared for those ‘what-ifs?’

I just beg everybody I know, ‘Buy the insurance.’ Yeah, it costs a lot. But it will save you 10 times more, and a headache.

I think that’s most of what I believe in. Of course I believe in education.

I’m proud of what you’re doing. I am extremely excited to see this come to fruition.

I can remember when somebody told me that my mother was proud of me getting a PhD. That thrilled the hell out of me. I am happier for you doing and taking your lead than my mother could have ever been with me getting a PhD. It was the third degree. But it’s just so wonderful to see you looking into and going forward with doing something that will help not only you, not only yours, not only future generations in our family, but also somebody else. So that’s your giving back. Thank you.

This is beautiful. Thank you for being so open.

Absolutely love hearing the stories from people of all walks of life on their journey / pursuit of true wealth (financial, physical, mental-emotional, spiritual, social). Thank you for being vulnerable and sharing!!!