“In order to understand my train of thought you’ll have to put yourself in my position. You can’t expect me to think like you cuz my life ain’t like yours.” — Clifford “T.I.” Harris

I used to debate co-workers about tipping.

I realize now how big of a mistake that was.

Most of them were white. Most were men.

They will never experience or understand how unpredictable at best and abhorrent at worst attitudes within the service industry can be toward Black people.

It precludes them and others from forming a complete picture. It disqualifies their opinion, at least during any discussion with me on America’s absurd tipping culture.

They’ll never know what it’s like walking into a restaurant and feeling like a ghost, waiting on a server to acknowledge your existence.

Or the feeling of being seated only to watch the wait staff attend to every table but yours.

Or not receiving bread other tables are enjoying. Or refills getting skipped. Or food orders taking forever.

Yes, slow, inefficient and downright rude service happens to everyone. But when you’re Black, bad service is much too common to be a coincidence.

There’s a long-standing stigma that Black people aren’t good tippers. Some believe Black patrons warrant poor service solely based on that negative perception.

If we want to play that game, let’s normalize Black people tipping relative to both the treatment we receive and the massive pay gap disparity we suffer from.

Our compensation never is challenged despite being a fraction of our white colleagues’, yet plenty of noise circulates about Black people allegedly being tightwads as tippers.

I know some family and a handful of Black friends who go out of their way to overtip. As if signaling to the service workers that not all stereotypes have substance. I used to do it myself. But then I stopped.

My actions can’t speak for or represent an entire segment of the population. More than that, I shouldn’t have to pay more than anyone else to receive base-level treatment. At that point, it feels like I’m paying for a positive perception of me. No thanks.

I have other family members and a handful of Black friends who constantly go out yet constantly complain about the experience, be it the food or the service. Sometimes both. They’ve also boasted of leaving a smaller tip because of their treatment, sometimes even writing a scathing word of advice as a “tip.”

A better solution is to abolish the practice of tipping. We’re better without it.

Everyone can’t be expected to understand or care about how tipping amplifies classism. Not even when presented as an exploitative labor practice, which places the onus on the customer rather than the restaurant owner to make up the difference between the wage a server gets and the wage that person earns, will most think twice about tipping.

But now that the custom is out of control, I’m seeing a shift. After all these years, I’m finally seeing mainstream America come to my side.

Suggested tips have infiltrated kiosks everywhere. Your to-go order that you drove to, got out of the car for and picked up? Yup. You’re being asked to tip and shamed into pressing the “no tip” button if you dare buck the shameful custom most Americans misguidedly consider to be “etiquette.”

I landed in Cleveland for a work trip in January and stopped at my beloved Shake Shack before leaving the terminal. Although humans were present, orders were placed on kiosks. I punched in my SmokeShack. Sure enough, before paying what I owed, I was prompted to leave a tip.

At many restaurants, gratuity isn’t even suggested anymore. It’s an obligation, automatically included in the bill. That was the case at dinner Tuesday night at Black Walnut in Oklahoma City.

Back in February, my bill at Virtue in Chicago had the audacity to include a 3.5% charge for insurance and benefits.

So not only am I paying employee salaries for restaurant owners, but I’m supposed to pay insurance and benefits too now?

Last November, at my favorite chicken wing spot in Oklahoma City, I asked a bartender about her experience with tipping. She told me people tip much less after the pandemic. She thought it stemmed from hardened personalities. My thoughts drifted more to higher prices.

Finally, I asked the woman what would be the harm in the restaurant industry abolishing tips and paying workers a livable wage.

Her answer: taxes. There’s more benefits, the bartender said, to being a tipped worker, although the woman didn’t explain how.

So now I’m supposed to subsidize service workers and help them get tax breaks?

I’ll gladly just pay more for my chicken wings, like they do in other countries that include service charges in the bill. If most of the world can survive without tipping, America civilization will march on.

Yet much of the pro-tipping crowd’s argument centers on “if you can’t afford to go out to eat, stay home.” All the while, consumers continue to allow restaurant owners to guilt their patrons into paying their employees’ wages that they’re not paying.

Of course, any honest conversation about tipping can’t be had without examining its history, which is where you high-and-mighty tippers might be in for a shock.

If you don’t know anything about the history of tipping, do yourself a favor. Listen to NPR’s podcast Throughline’s. Its episode on tipping, titled “The Land of the Fee,” provides valuable context. It might change your perspective on tipping.

The episode features an interview with Nina Martyris, a journalist who has written about tipping’s history. In the first 15 minutes, she unraveled how tipping was unpopular in America in the 1800s and why many found the practice distasteful.

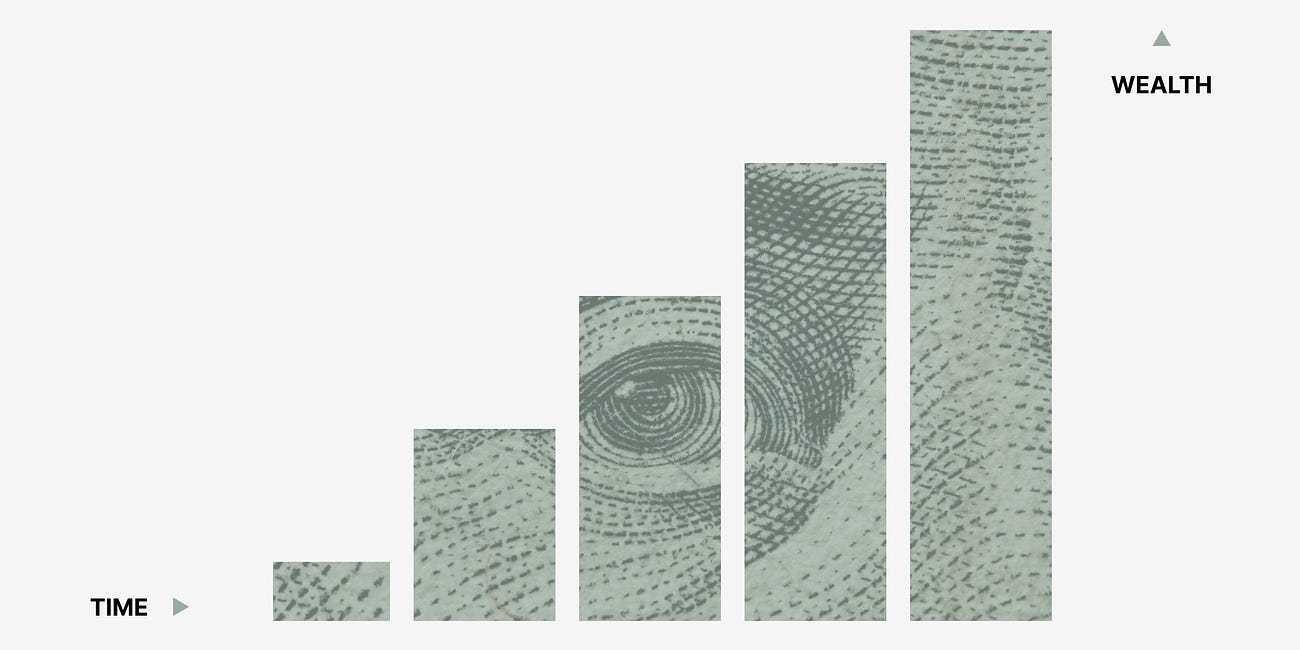

“When you give a tip, you establish a class system,” Martyris said. “And what is a class system? It is a class system of superiors and inferiors…By tipping someone, you rendered him your inferior. Your moral inferior. Your class inferior. Your economic inferior. So it was a caste-bound system.”

It was a system popularized after the passage of the 13th Amendment and the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, which freed approximately 4 million formerly enslaved people. Those people — Black people — had no jobs, no land, no education and were in need of work.

American businessman George Pullman pounced, hiring Black men who were former slaves to be porters for his railroad company’s sleeping cars. They provided elite service and were compensated only in tips.

The restaurant industry soon followed, using the tipping method as a means to get away with paying low wages.

We’ve simply allowed a custom rooted in classism to snowball into its current out-of-control state, a toxic climate of stereotypes, shaming and subsidies, all swelling in size.

Something to think about the next time you’re prompted to pony up 20%.

For me, this is a long awaited Money Talks entry that was truly worth the wait. Makes you go “Hmmmm!!!” Your title belies the depth, seriousness and pertinent of the matter. Now I need to rethink and rationalize all that you have shared with us, and determine my course of action - - keep Tipping, modify my Tips, stop Tipping in those ridicules elevator-like situations, or stop Tipping all together. Maybe, for every satisfying meal, well performed service, uplifting experience I have, I will donate that 10, 15, 20 or 20+ percent of what I was just blessed to be able to spend on myself to a charitable cause that helps those who are still locked in those “lower class” situations that still exist. “Rethinking Tipping”

I’m definitely one of those who sometime overtip because of the perception. It’s hard to get away from sometimes.